The landscape of indirect tax is currently undergoing a significant technological metamorphosis. Many tax authorities require submitting and storing transactional and tax-relevant data electronically.

Requirements are complex, and so is the terminology. These terms are not always harmonized across the market, leading to confusion even within this industry. This guide offers insight into Fonoa’s terminology definitions. It aims to make things easier by explaining the terms often used in indirect tax compliance space and how they relate to each other.

Indirect Tax Controls

These are governmental controls - performed by tax authorities - applied to processes related to indirect taxes, such as Value Added Tax (VAT), Goods and Services Tax (GST), and Sales and Use Tax (SUT) etc. These controls constantly evolve worldwide and require taxpayer’s careful examination to ensure compliance. Digital Reporting Requirements (DRR) and Post-Audit Requirements (PA) are under this umbrella.

Digital Reporting Requirements (DRR)

This is a relatively new term relevant to EU countries that the European Commission introduced with the VAT in the Digital Age Report (ViDA) initiative. Digital Reporting Requirements (DRR) are any obligation for a VAT-taxable person to periodically or continuously digitally submit data on all or most of their transactions to the relevant tax authority. There are two types of controls: continuous and periodic.

Continuous Transaction Controls (CTC) require taxpayers to submit fiscally relevant data to the tax authority or a delegated platform before or shortly after the transaction occurs.

Periodic Transaction Controls (PTC), on the other hand, are obligations requiring taxpayers to submit transactional data periodically, i.e., on a monthly, quarterly or annual basis (periodically rather than in real-time).

Post-Audit Requirements (PA)

Post-audit invoicing requirements are a type of indirect tax control where authorities are not involved in the exchange of invoices and do not require transactional data submission. Tax authorities can audit the compliance of such processes after invoices are issued. Post-audit requirements contrast with CTCs, as the latter entails that the authority’s control happens at the point of clearance or in real-time/near real-time. This does not mean, however, that taxpayers cannot be subject to audits in CTC systems.

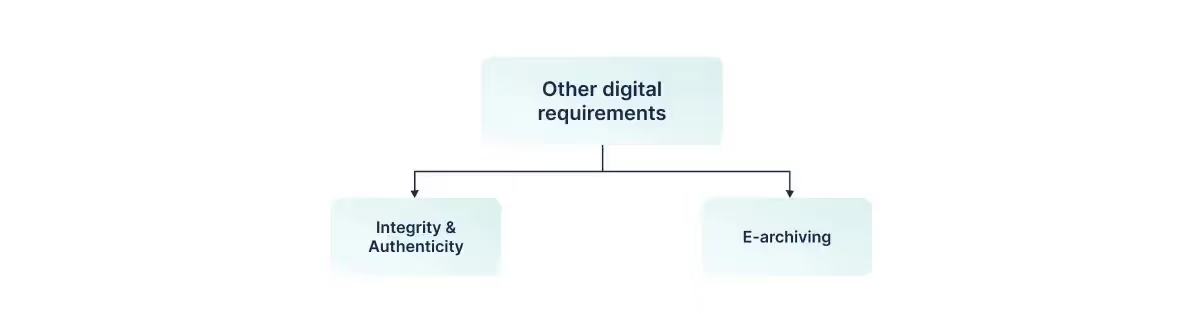

Other Digital Requirements

Other digital requirements are relevant for both CTCs and PTCs. This category requires generic digital requirements such as ensuring integrity and authenticity (I&A) and e-archiving.

“Integrity of content” means that the required invoice or document content has not been altered, and “Authenticity of the origin” means the assurance of the supplier's identity or the issuer of the invoice or document. From the point of issuance until the end of the storage period, the I&A of electronic documents must be ensured. Depending on the country, transaction types, and process, different methods can ensure I&A.

One of the most common methods is to sign digital documents using digital signatures and seals. For example, in the Dominican Republic, Panama, and El Salvador, issuers must apply a digital signature on e-invoices to comply with local I&A requirements. In the EU, while ensuring the I&A of e-invoices is required, taxpayers may generally choose how to do so. The application of an electronic signature or seal based on a qualified certificate holds the highest level of security and presumption of reliability. The invoice issuer may, however, adopt other methods, such as business controls-based reliable audit trail (BCAT) and electronic data interchange (EDI).

E-archiving is a common requirement for the storage of electronic documents. Due to their fiscal and legal evidence capability, compliant storage of electronic tax documents is an important - yet often ignored- part of the compliance process. Amongst others, e-archiving regulations frequently focus on storage length, location, searchability, backup, I&A during the storage period, the naming of stored documents, and outsourcing of e-archiving and access.

Breaking down Periodic Transaction Controls (PTC)

Periodic Transaction Controls (PTC) require taxpayers to submit tax-relevant data on a periodic, e.g. monthly, quarterly, annually, or on-demand basis. SAF-T and VAT listings are two examples of PTCs.

Standard Audit File for Tax (SAF-T)

SAF-T stands for Standard Audit File for Tax. The OECD developed the standard. However, countries that implement SAF-Ts have their own SAF-T specifications. Some countries implemented SAF-T as a monthly (e.g. Portugal billing SAF-T), quarterly (e.g. Poland) or annual (e.g. Portugal accounting SAF-T) file submission requirement. Countries like Austria and Norway require on-demand SAF-T submission to the tax authorities.

VAT Listings

A VAT listing breaks down the VAT return to a level where each transaction is reported separately to the tax authorities. It often follows the VAT return submission deadlines. EC sales list could be considered an example of a VAT listing obligation in the EU.

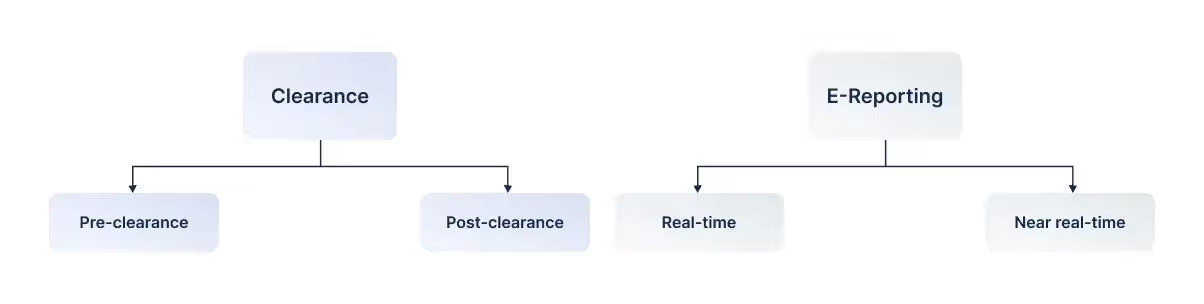

Breaking down Continuous Transaction Controls (CTC)

Continuous transaction controls (CTC) are defined by the frequency and timeliness of data submission to the tax authority for approval. Whereas in PTCs, data is submitted periodically, CTCs require continual and consistent presentation at a transaction level. Two types of CTCs will be discussed: Clearance and E-Reporting. The main relevant differences between country-specific regulations are:

- When data must be submitted

- What data must be submitted

- How data must be submitted

- Who delivers data to the recipient

When data must be submitted

Clearance

In clearance invoice models, documents gain legal and fiscal validity only after they have been validated and cleared (approved) by the tax authority. The specific method of clearance can vary across different jurisdictions. For instance, it might involve assigning a unique number or UUID, as in Poland, or applying an electronic seal or a token by the tax authorities, such as in Mexico.

The timing of the clearance process in these systems can vary; it may occur before or after the business documents are exchanged between parties. For instance, in Poland, Brazil, and Italy, taxpayers must submit their invoices to the tax authorities for clearance before these documents are sent to their trading partners (pre-clearance). On the other hand, in Peru and Uruguay, the tax authority performs the clearance of the invoice after it has already been issued and exchanged between the trading parties (post-clearance). In such cases, the e-invoice holds conditional validity until it receives formal approval from the tax authorities.

E-reporting

In E-Reporting systems, taxpayers must provide transactional data to the authorities in real-time or near real-time in relation to when the transactional document was issued. In Portugal and Hungary, for example, invoice data must be reported to the tax authority immediately after issuance (real-time). While in Spain and the Philippines, taxpayers have a few days to report the data.

What data must be submitted

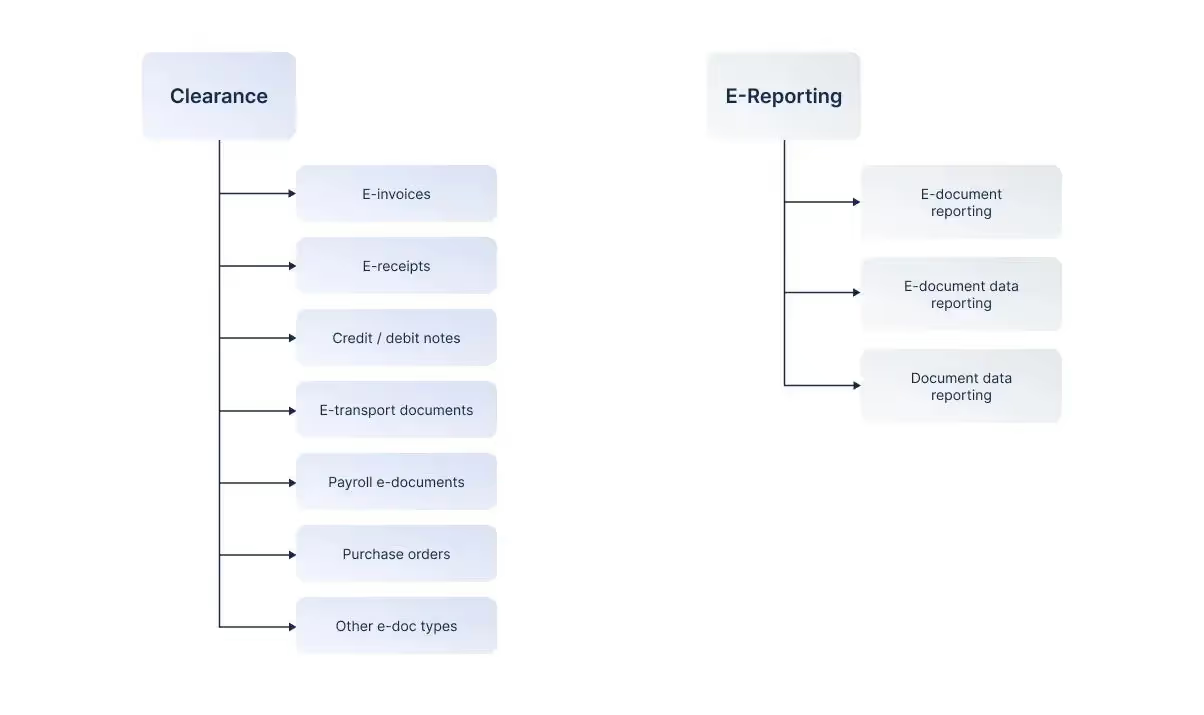

Clearance

In clearance systems, the validation and clearance by tax authorities is essential for the legal and fiscal validity of e-documents. Countries that implement these systems may include a wide range of e-documents that must be cleared, such as purchase orders, e-invoices, credit/debit notes, e-receipts, and e-transport documents. The specific types of documents required can vary across different jurisdictions.

E-reporting

On the other hand, E-reporting systems differ from one another in two different ways. First, whether it is mandatory to issue documents in electronic format, and second, whether the complete document or a subset of the document needs to be submitted.

For example, in South Korea, taxpayers are obliged to both issue invoices electronically and report the entire document to the authorities (ie. E-Document Reporting). In contrast, countries like the Philippines require taxpayers to submit only a subset of data after issuing an electronic invoice (i.e. E-Document Data Reporting).

There's also a third approach, in which taxpayers are not required to issue documents electronically but must report a subset of their data in electronic format (i.e. Document Data Reporting). Countries like Portugal, Spain, and Hungary have adopted such e-reporting requirements, even though electronic invoicing is not compulsory there.

Since there is no pre-validation of the invoice in an e-reporting system, as in clearance systems, if the reported document does not pass the authority's checks due to substantial mistakes, the invoice may need to be reissued and the recipient notified.

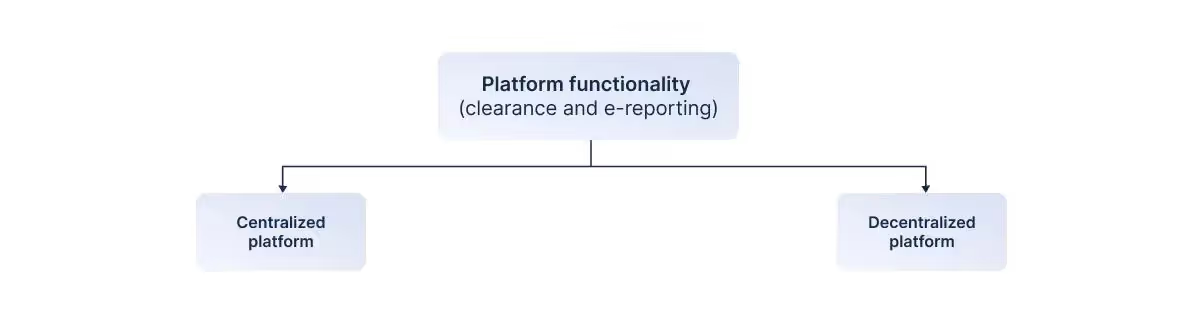

How data must be submitted

The “How” diagram portrays the platform functionalities in CTC systems, explaining how to submit data to the competent authority. It is divided into Centralized and Decentralized platforms. In this diagram, clearance and e-reporting CTC types can be analyzed in conjunction.

Centralized Platform

Most countries only allow taxpayers to submit data for clearance and/or e-reporting via a single centralized designated platform or endpoint. For example, this is the case for Poland, where the National System of e-Invoices (KSeF) is the only platform to submit e-invoices for clearance. The centralized e-invoicing model exists in countries with e-reporting mandates, such as the Philippines, where transactional sales data is reported via the E-invoice/E-receipt System centralized platform, and in Spain, where document data is reported directly to the tax authority (AEAT).

Decentralized Platform

Some countries, however, allow or require taxpayers to submit their data to authorized service providers. These providers are private entities, are usually local, and have been certified by the Tax Authority. These decentralized platforms take charge of validation and clearance, ensuring integrity and authenticity, and sending the data to the tax authority. This model is adopted in Mexico, with the Authorized Certification Providers (PACs), and in Peru, with the Operators of Electronic Services (OSEs).

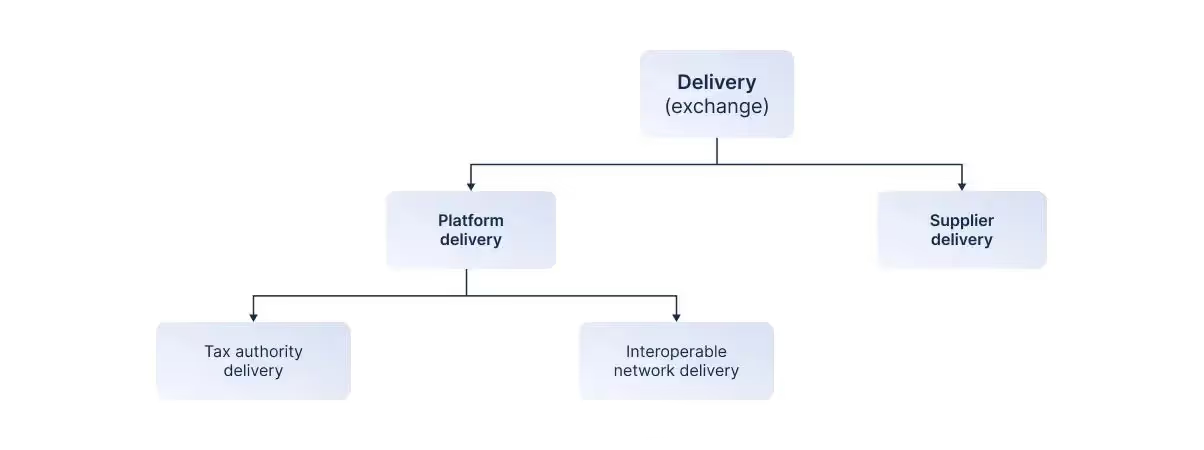

Who delivers data to the recipient

The “Who” diagram illustrates the different avenues through which the parties to a transaction can exchange an e-document, highlighting two primary pathways: “Platform Delivery” and “Supplier Delivery”.

CTC models can vary in who is responsible for exchanging or delivering the data to the recipient. Generally, either the platform or supplier will be responsible for delivery.

Platform Delivery

With Platform Delivery, no action is required from the issuer to promote the e-document exchange. A designated platform carries out e-document delivery after the applicable validations take place. There are two types of platform delivery.

Tax Authority Delivery happens when the official central government platform facilitates transmission. This is the case, for example, in Turkey and Italy, where the Gelir İdaresi Başkanlığı (GIB) and the Sistema di Interscambio (SdI), respectively, are responsible for delivering the cleared e-invoice directly to the document recipient via available delivery channels. This may be done via an Application Programming Interface (API) or in a taxpayer private portal.

Interoperable Network Delivery refers to the exchange via a network of private service providers, such as Peppol or the French Partner Dematerialisation Platforms (PDP), which enables communication between the diverse systems used by suppliers and buyers. In this model, the regulator focuses on establishing a unified document format and exchange methodology for businesses to gain efficiency and for regulators to perform audits and analyses.

Supplier Delivery

The second exchange pathway is the Supplier Delivery, in which the issuer delivers the e-document directly to the recipient. Local regulations may allow the parties to agree on document form and the distribution method, which is the case in Brazil, Colombia, and several other countries. Countries such as South Korea require that delivery happens specifically via e-mail.

In the case of E-reporting mandates, the transactional document exchange (e.g. invoice) usually happens before or at the same time as the data e-reporting to the authorities. Such transactional documents are commonly issued and exchanged per Post-Audit requirements. Under the diagram “Invoice Exchange” in the section “Invoice Post-Audit Requirements” further explanation is provided.

Breaking down Post-Audit Invoicing Requirements

As explained, Post-Audit Invoicing Requirements pertain to tax authority controls being exercised post-invoice issuance.

Although post-audit requirements may seem less stringent than the controls imposed by CTCs, they still require elaborate compliance efforts from taxpayers. These requirements may vary for invoice generation, format, content, and delivery. Examples of Post-audit invoicing requirements applicable in various countries and at different stages of the invoice issuance process are provided below.

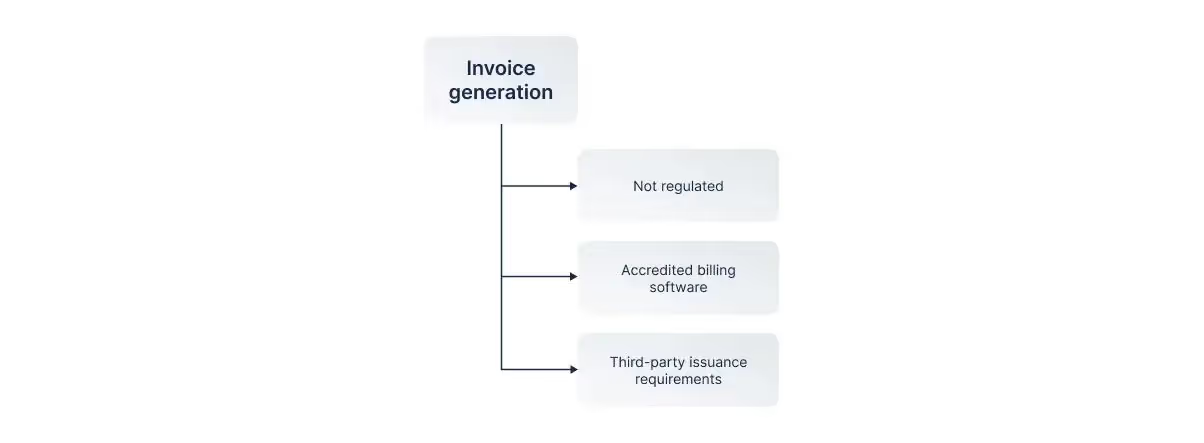

Invoice Generation

It is common in Post-audit jurisdictions that invoice generation is not regulated, meaning that taxpayers may utilize any means to generate the invoice. Taxpayers can choose from a selection of billing software available in the market or generate from in-house software, for example.

However, some countries have imposed limitations to ensure that invoicing software complies with a certain level of security and reliability. For example, Portugal requires that certain taxpayers issue invoices and other fiscally relevant via billing software certified by the local tax authority. Mainland Spain and the Basque Country have also followed this approach.

Another requirement often observed in countries with a post-audit model is specific to third-party issuance and the rules that may apply in such cases. This may include establishing an explicit private agreement between the taxpayer and the third-party issuer (required in most EU countries) and providing authorization before the local tax authority (required in Spain).

Invoice Format

In Post-audit countries, taxpayers are generally free to issue invoices in any format as long as the chosen format ensures the legibility of the document. This flexibility allows taxpayers to issue either paper or electronic invoices, provided they adhere to the invoice content requirements stipulated by local regulations.

Following this freedom of format, taxpayers are often allowed to issue invoices as PDFs, considered electronic invoices (despite not being in a structured/machine-readable format, such as XML), on the condition that the trading party consents to receiving e-invoices.

However, it should be noted that in a limited number of countries, paper format is still predominantly used for issuing invoices. In jurisdictions like Israel, transitioning to electronic invoices might necessitate prior notification to the tax authorities.

Invoice Content

Invoice content requirements are usually regulated by tax or commercial regulations. Post-audit requirements will vary, from assigning a sequential and unique numbering on invoices to applying a unique “hash” to create a chain of all issued invoices.

In Finland, for instance, invoices only need to contain a unique sequential numbering assigned by the taxpayer. However, in Portugal, invoices and other fiscally relevant documents must have a Unique Document Code (ATCUD) obtained from the tax authority and a QR code. In the Basque Country, taxpayers must use a billing system that applies a “hash” to ensure the uniqueness of invoices.

Regarding invoice language requirements, EU countries generally allow using foreign languages. Still, they may require a translation into the local language in certain instances during audits, as stipulated by the EU VAT Directive (e.g. Belgium). In contrast, some non-EU jurisdictions mandate that taxpayers issue invoices in the local language (e.g. China), while others permit using foreign languages (e.g. Japan).

Additionally, taxpayers may be obliged to adhere to specific foreign currency and exchange rate requirements. This is crucial to ensure the accurate conversion of tax and total amounts into local currencies, as applicable laws require.

In Japan, taxpayers must acquire a specific issuer status to generate VAT deductible invoices, known as Qualified Invoices, and include their registration number as part of the invoice content.

Invoice Delivery

There are usually no specific requirements regarding how the transacting parties must exchange invoices in Post-audit countries. The most common approach is allowing them to agree on the preferred invoice delivery method from issuer to recipient.

Some post-audit countries have started to turn to interoperable networks as an optional means of invoice exchange without imposing any clearance requirements from local tax authorities. This is usually done by joining Peppol and becoming a Peppol Authority. However, taxpayers who exchange via the network must do this in the applicable Peppol electronic billing format.

Additional Resources

- Looking to learn more about DCTR and e-invoicing? Look at this article explaining e-invoicing models with a focus on the 5 Corner Model.